In the Northern Territory, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cognitive impairments are being indefinitely detained in prison despite not being charged.

In the Northern Territory, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cognitive impairments are being indefinitely detained in prison despite not being charged.

In 2014 the Australian Human Rights Commission found that the inability of both the Commonwealth and Northern Territory Governments to provide adequate accommodation and support services for four Indigenous men with disabilities (all of whom were deemed unfit to plead and detained in a correctional facility) constituted a clear abuse of human rights.

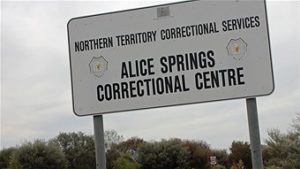

One of the men spent more than four and a half years detained in the Alice Springs Correctional Centre before being transferred to a secure care facility; however, if he had been found guilty of the offence with which he was charged, the Court would have imposed a term of imprisonment of 12 months.

While the lack of screening and diagnostic tools means there is no definitive data on the total number of Indigenous people with cognitive impairment in the criminal justice system, expert opinion and estimates suggest this group is significantly over-represented compared to the general population.

As part of a study about Aboriginal people with psychiatric and cognitive impairments in the NT and NSW, University of NSW researchers found that “police and prisons have become governments’ default way of managing this vulnerable group rather than appropriately supporting them to have a life of stability and self-worth in the community”.

So why is this happening? First, current legislation does not protect people with cognitive impairment charged with lower level crime.

Although there are legislation and schemes in the lower courts (i.e. Court of Summary Jurisdiction) that “may be relevant to a person with a cognitive impairment”, unfortunately most of these schemes focus on the needs of people with a mental health problem, which are generally quite different to the needs of cognitively impaired people, states one analysis.

The Criminal Code Act stipulates that the Supreme Court must decide whether someone found not guilty due to mental impairment must be either liable to supervision (custodial or non-custodial) or released unconditionally (‘mental impairment’ in the Act includes ‘senility, intellectual disability, mental illness, brain damage and involuntary intoxication’).

Unfortunately, according to criminal lawyers Michelle Swift and Jonathan Hunyor, people are rarely released unconditionally, and the lack of appropriate facilities in the NT to house people on custodial supervision orders often sees people with cognitive disabilities indefinitely detained.

In 2012, the Aboriginal Disability Justice Campaign found that all of the nine people who were on a supervision order due to mental impairment were Aboriginal.

This situation is compounded by mandatory sentencing in the NT, which significantly limits the court’s ability to take a person’s disability into account in determining an appropriate sentence.

For relevant offences, the court can no longer take account of a symptom of disability (such as poor impulse control) as a contributing factor in offending. Nor can the court consider the particular impact of imprisonment on a person with a disability.

In its paper on the indefinite detention of Aboriginal people found unfit to plead, the Aboriginal Disability Justice Campaign argues that a sentence of imprisonment imposed on a person with a cognitive impairment may be inappropriate and ineffective because the person may not fully understand the connection between the offending behaviour and the prison experience.

As well, in some cases a person with a cognitive impairment may ‘do it harder’ in prison because of difficulty understanding the rules of prison and the experience more generally.

In most cases prison offers a poor therapeutic environment, and fails to support the particular needs of this group.

As well, there is a key difference between mental illness (such as depression, personality disorders, psychosis and schizophrenia) and cognitive impairment (such as intellectual disability, acquired brain injury, dementia and foetal alcohol spectrum disorder).

Mental illnesses may be episodic and can be treated, whereas cognitive impairments are ongoing and permanent. They affect intellectual functioning, including comprehension, reasoning, learning and/or memory.

The model for treating mental illness is neither appropriate nor effective for people with cognitive impairments.

Too often, according to NSW researchers, support focuses on offending behaviour – rather than addressing social disadvantage, mental health, disability or alcohol and drug issues.

Exacerbating this is the lack of adequate services available for workers in the criminal justice system (lawyers, corrections officers, magistrates, etc) to support comprehensive and culturally appropriate assessments.

Cognitive impairment requires highly specialised assessments and support programs; however, current arrangements in the NT mean that these sorts of programs are sorely lacking.

In addition, Aboriginal people with cognitive disabilities have the added complexity of the impact of intergenerational trauma, grief, loss and locational disadvantage. Colonisation and discriminatory government policies have seen generations of Aboriginal people experience racism, dispossession, early deaths of family and community members and the forced removal of children.

Finally, there is a chronic lack of alternative options to prison for people with cognitive impairments. The shortage of appropriate prison-based support and post-release programs increases the likelihood this vulnerable group will return to prison.

Aboriginal people with cognitive disabilities, particularly those living in remote communities, have limited community-based support options, which can exacerbate feelings of isolation and disconnection.

In failing to offer alternative options, the system discriminates against people with cognitive impairments and sees them exposed to the justice system for longer periods of time than those who are criminally charged.

The pathway into prison for Aboriginal people with cognitive impairments is predictable but preventable. Steps must be taken immediately to ensure the justice system truly meets the needs of people with cognitive disabilities in culturally appropriate ways, with a focus on therapeutic responses.

In response to the Senate inquiry into the indefinite detention of people with cognitive and psychiatric impairment, Jesuit Social Services is calling for an end to indefinite detention by reforming the justice system to better meet the needs of people with cognitive impairment.

This can be achieved by improving screening tools, amending legislation, expanding specialised problem-solving courts and providing a wider variety of therapeutic, community-based alternatives to prison.

Aboriginal people with cognitive impairments are entitled to opportunities to engage meaningfully in society and to flourish as individuals. More must be done to stop this discrimination and clear abuse of human rights.

This post is written by Julie Edwards, CEO at Jesuit Social Services.

This post was originally published at Croakey.